There has been significant discussion recently on the concept of the “virtual cell.” I want to summarize the key concepts regarding what the field wants from a virtual cell and the challenges we face. In particular, the current trajectory reminds me of the evolution of statistical genetics (GWAS) and Mendelian disorders—analogies that I believe point to the most likely path for the field’s development.

What people want in a “virtual cell”

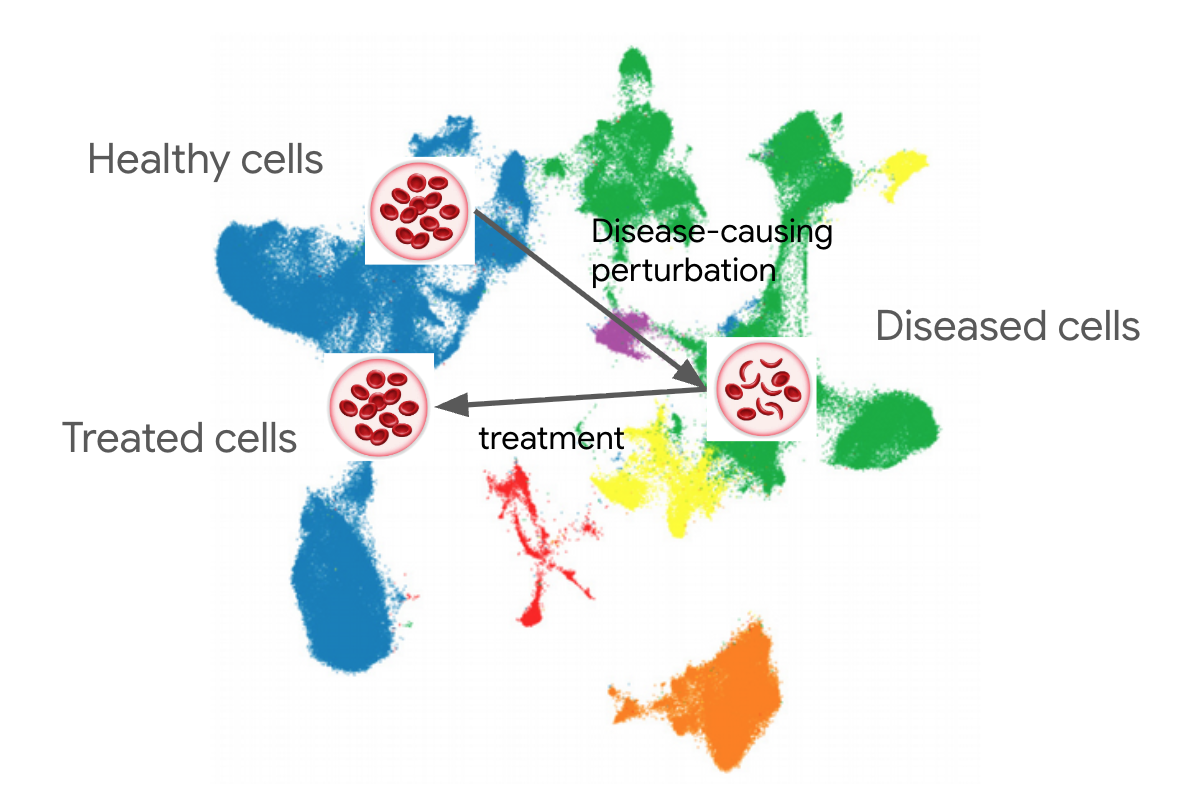

What do people mean when they say “virtual cell”? From listening to descriptions of what it will achieve, I think they want a model which lets them position every healthy cell and any disease on a coordinate map, so they can represent any disease causing effect as a path on that map, and that map will then indicate the treatment paths that move back to the healthy state.

The “virtual cell” as currently discussed centers on the transcriptome, with several large public datasets of a few cell lines with genetic or drug perturbations, with some datasets overlaying spatial data (spatial transcriptomics) and some including other imaging.

Tied with the push toward a virtual cell are efforts to build a foundation model that trains on all of the available data to construct this map. I think implicit in this is the hope to replicate AlphaFold’s combination with extensions to inform broad applications in ligand binding, antibody design, predicting protein complexes, and understanding variant effects.

However, I don’t think the experience with transcriptome foundational models will manifest in that way. I think the experience will look more like how we use GWAS.

Why are people excited and why is this area is very hard

Breakthroughs in models are preceded and enabled by breakthroughs in data collection methods combined with breakthroughs in metrics that allow their measurement. AlphaFold depended on PDB structures and CASP evaluations, ImageNet contained both the data and metrics needed to nucleate the deep learning for image classification. The combination of genome in a bottle data and comparators enabled substantial improvement in sequence methods, as well as analysis methods like variant calling and genome assembly.

One reason for excitement is that we have major breakthroughs in data generation. The cost to barcode cells and sequence RNA at scale has fallen dramatically, companies are competing on solutions that with a single run simultaneously image a slide. Proteomics assays are scaling into this space. Which is one reason multiple efforts have formed to build something like the ImageNet for the transcriptome.

I agree this is very exciting. And I love how open the datasets have been. But there are two areas where we still have obstacles to overcome. The first is that experimental batch effects are very strong in these assays. Which sequencer you use, which kits you use, how you prepare the RNA, how you handle the cells before preparation can all have large effects. So the majority of the difference between two datasets can be effectively “non-biological” in the sense that what you would learn doesn’t correspond to the parts of the biology you want to learn.

This interacts with the second problem. Our metrics to understand model quality are still weak. Metrics like “how well did you reconstruct the dataset” run into the issue that doing well on that is a lot about modeling the specifics of the assay error. Other metrics like “predicting cell type” have an issue that what the label is often is artificial (e.g. what is a “cell type”).

You might think I am pessimistic about this area. That’s not the case, I’m very excited. But I think the ways these models will be best used will follow a specific path.

Lessons from Mendelian Genetics and GWAS

This reminds me of another area which involves noisy, high dimensional data, which sits at the interface of the genome and the environment, and is enabled by a few large scale datasets - Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS).

In GWAS, we have noisy measurements of phenotypes where researchers ask specific and controlled questions about the correlation of genetic factors and those phenotypes. A rich field has developed around the right ways to isolate confounding factors and get the clearest statistical links. There are a few foundational datasets, most notable is UKBiobank, the scope, scale, and broad availability to scientists, has been extremely enabling.

Statistical genetics has proven useful for drug discovery (PCSK9 inhibitors being a clear example) and target validation. But it has been very difficult for genomic foundation models to contribute to the association component. Because of the number of genome variants relative to sample numbers, models overfit faster than they learn generalizable information. There are starting to be some demonstrations of this, but the field has achieved a great deal without using foundation models for the association component.

The savviest operators in this space actively use UKBiobank (or in cases like Regeneron larger general cohorts) to understand associations in the general population (especially for more prevalent diseases) and then actively construct cohorts of interest, enriching for particular diseases or in populations. They use ML models to improve phenotype labels (where there has been a lot of success), and use genome models like Enformer, AlphaGenome, SpliceAI, etc… to help interpret the hits that they find. A similar approach is used in rare disease to aggregate similar cases, find, and interpret the causal variants.

In short, they use broad public models and datasets to focus and improve the power of the full public-private datasets that they construct to answer specific biological questions.

How success will likely manifest

I think the best future use of transcriptome models will follow a similar path. The savviest operators will focus on how to extract the generalizable components of public datasets and models, whether by taking embeddings and finetuning them for their data, or by focusing on transferability methods designed to translate from the public data to their data.

In this approach, research groups will get the most value out of constructing their own datasets to answer specific questions (for example about a specific disease or cell line of interest, or in their own compound libraries), which will be informed and supplemented by broad foundation models.

Lessons for the field

If this sounds reasonable, what lessons are there? On the modeling side, further developing the ability to explicitly identify, isolate, and subtract confounding noise is a great direction. Also building evaluation metrics that can be more tied to clear, objective biological properties of interest will help move more towards the ImageNet exemplar.

On the research demonstration side, the most useful early demonstrations will be the ones that more tightly link the data or model with biological insight. So aim for papers where the result advances understanding which can be supported by orthogonal validation.

Another area will need to be less focus on what the “best” model is. It is tempting to judge the quality of work on the basis of a specific F1, and papers will surely show outperformance. But because we are so early in establishing the best metrics and understanding how to use the papers, maximizing score on a metric will be less useful than new insights about biology that can be supported by that orthogonal validation. As an aside, I think that the “general genome language model” domain also has this same property.

On the data generation side, in addition to generating extremely large datasets, it will be important to focus data generation in cell lines, perturbation domains, or disease areas that will enable us to ask specific questions about the biology.

In short, in addition to the instinctive draw toward making very large and broad datasets, the ability to distill and focus that to answer specific biological questions will be most important to build trust for virtual cell models to advance our understanding of biology.